Prostitutes in Antiquity

Back in the time of Jesus, "prostitutes usually were slaves, daughters who had been sold or rented out by their parents, wives who were rented out by their husbands, poor women, exposed girls, the divorced and widowed, single mothers, captives of war or piracy, women bought for soldiers – in short, women who could not derive a livelihood... In Palestine, torn by war, colonial taxation, and famine, the number of such women must have been great." - Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza "In Memory of Her" (1998 edition), p.128

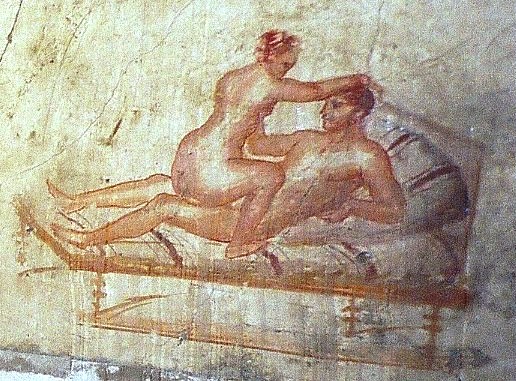

The topic is vast but in terms of representations in art, here are a few indirect references: the Sirens, Lot's wife, Roman brothels, and Byzantine courtesans. To focus here just on Roman art, in Pompeii, the brothel is still a very popular spot for tourists, although when I visited it, it seemed to be tucked well away from the popular walkways:

Not all buildings containing erotic art were for prostitution of course, but erotica - for better or worse - was woven into daily life in Roman cities, and sexual activities were not that different from today. The penis, for example, was a symbol of fertility known to ward off evil spirits and it was used in store signs, particularly outside bakeries and private houses. Now that hasn't changed. :)

Most erotic antiquities from Pompeii and Herculaneum ended up in the National Archaeological Museum in Naples (Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli). The antiquities have been available to view intermittently over the centuries (the Bourbon rulers of the 18th century were avid collectors). Since 2000 they have been fully accessible in the “Gabinetto Segreto” (Secret Room - link here). You will see images like this famous statue of Pan (and goat), which was found in the Villa dei Papiri in Herculaneum in 1752, and the tintinnabulum below that, which was a good luck wind chime, on the theory that laughter drives away evil.

If we jump forward to the Renaissance, we have male prostitution in Florence here, but Christian redemption plays a larger role. This painting below of Mary Magdalene is by Pietro Perugino around or before 1500, a few years before his contemporary Leonardo da Vinci painted the Mona Lisa. They both have the same faraway look and indeed this was originally attributed to Leonardo (and other painters over the years).

I think this painting below is underrated and it's by an underrated painter although he was one of the most respected artists of his day. It is based on his wife Chiara Fancelli and it is in the Pitti Palace, Galleria Palatina, Florence.

Perugino, as his name suggests, was from Perugia. He trained in Florence possibly alongside Leonardo and Botticelli and he was active there, in Perugia and in Rome. He was responsible for some of the wall frescoes in the Sistine Chapel (audiences usually ignore them as they gaze at the ceiling). He also was commercially successful (which seems to have exasperated Michelangelo) and one of his students was Raphael.

I chose the image above because it captures so well the Renaissance mix of sacrilege and redemption in the era of Savaronola - note Mary Magdalene's halo. Here, Noli me tangere applies to men, as if she were to say "Don't touch me." This line (translated here into Latin) was supposedly said by Jesus to Mary Magdalene during her first encounter with him after his Resurrection (John 20:17).