Poison Pen Letters

The Strange Tale of Agatha Christie

The Strange Tale of Agatha Christie

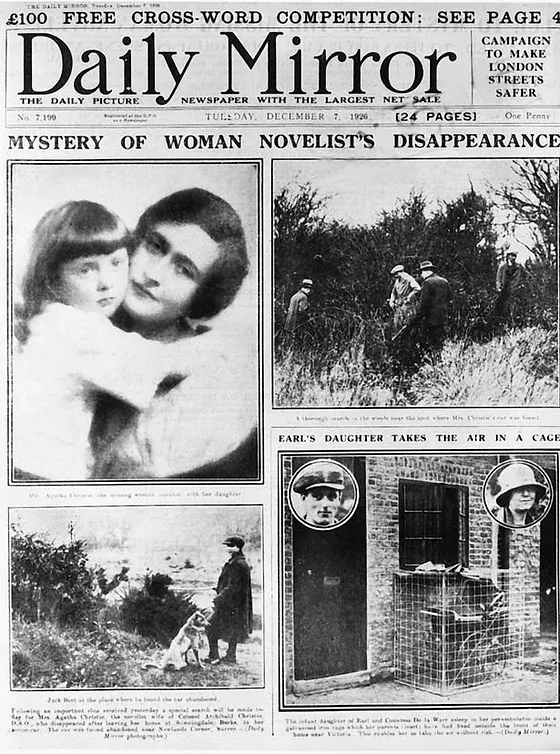

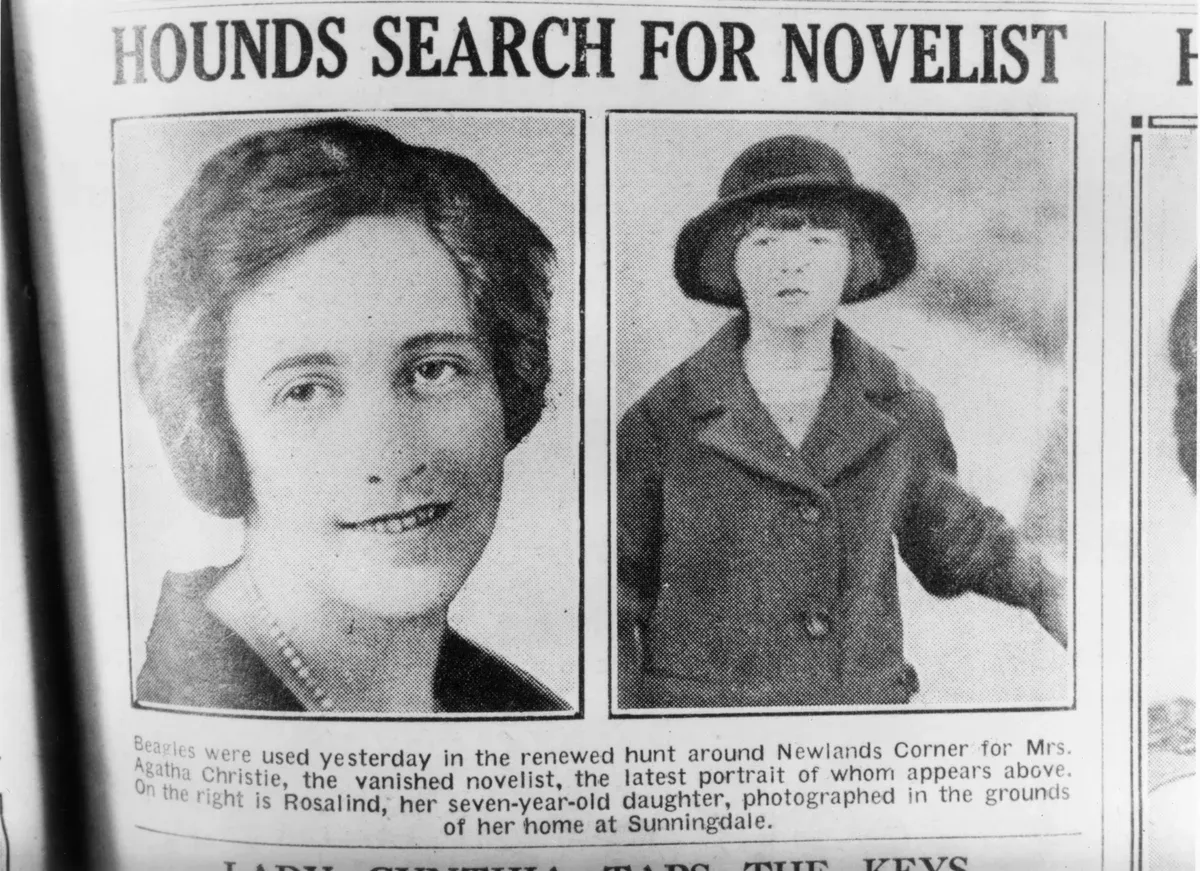

Once upon a time in the middle of a bitterly cold winter, a young Gypsy man was out walking near Guildford, southwest of London, when he found an abandoned car down an embankment and reported it to the police. It was early in the morning, a Saturday, in December of 1926. When the police arrived, they were able to identify the owner of the car from an expired driver’s license left inside, indicating that it was the famous writer of detective fiction, Mrs. Agatha Christie. Also left in the car were a fur coat and various personal belongings, which suggested that the driver may have left poorly protected against the cold. The police paid a call to the Christie house near Sunningdale, Berkshire, to inquire as to her whereabouts and were told by her staff that she had driven off after 10 p.m. the night before with no word on where she was going.

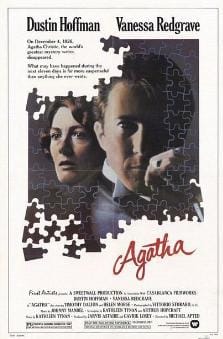

Agatha Christie was not “rediscovered” until 11 days later. What happened in the interim? How could one of the country’s most famous writers simply disappear and no one know what happened to her? There was intense speculation about her motives throughout the rest of December and into 1927. Then a wall of silence descended for half a century. In her autobiography of 1977, published one year after her death, Christie skates past it as if it never happened. In 1978, the subject was reopened with the publication of two books. The first, The Mystery of Agatha Christie was a biography by Gwen Robyns, and it was written without the cooperation of the Christie family, indeed it faced their active opposition. The second, Agatha, was a speculative novel by Kathleen Tynan that was subsequently made into the Michael Apted film of 1982 starring Vanessa Redgrave and Dustin Hoffman. A flurry of biographies followed, notably the authorized biography by Janet Morgan in 1984, and it is fair to say that they all have different theories about Christie’s disappearance. This is one mystery that has never been solved and it is better than any of her novels. The question then is, What exactly was it that she did and why did she do it?

A PUBLICITY STUNT

One of the first journalists to investigate was the 20-year old Lord Ritchie Calder. Although his job was to be curious about Christie’s disappearance, he also knew a good story when he heard one. Christie was a household name after her mystery novel The Murder of Roger Ackroyd became a cause célèbre earlier in the year. So the press gave her disappearance banner headlines in every newspaper in the country.

By the time Calder got on to the story, the police were dragging a small lake near where the car had been found and thousands of volunteers were fanning out over vast areas of Berkshire, Surrey and other counties. This particular lake, known as the Silent Pool, was interesting because it had put in an appearance in an earlier Christie story and on that occasion a young woman’s body had been found in it. Was Mrs. Christie staging one of her stories or was she in the pool, Calder wondered? The police dragged and dived it twice but came up empty. Calder knew from reading Roger Ackroyd that the story begins after a woman has committed suicide. At the same time, there were dozens of eyewitness reports, all of them contradictory, just like in a good Christie mystery. The press, the police, and the public were considering three possibilities at this point: (1) that the author of Roger Ackroyd had disappeared because she wanted to stage a publicity stunt that would further her own career, or (2) that she had committed suicide, or (3) that her husband had murdered her. Calder relished that last possibility -- imagining the Queen of Fiction murdered by her husband and her body hidden away behind the vicarage.

It wasn’t long before the police and press knew that Christie had suffered setbacks during the past year. Her mother, to whom she had been very attached, had died a few months earlier and Christie had gone to live in the old family house in Torquay while it fell apart around her. You could almost say that the house stood in as a metaphor for her own life; perhaps she suffered a partial breakdown? This was seen as nothing unusual for a woman of 36; most people experienced it at some stage of their lives. At the same time, her marriage to Archie Christie was coming apart. They had married during the Great War and Calder wondered if they had really been that compatible in the first place. After 12 years of marriage the Christies had a 7-year old daughter and financial security but absolutely no chemistry. By November, not long before her disappearance, Agatha Christie knew Archie was having an affair with Nancy Neele, whom Agatha had met once or twice. There are varying reports on what happened next but it appears that on the morning of Friday, December 3, Christie and her husband had an argument and he packed his bags to spend the weekend with Miss Neele in Godalming. Archie had apparently asked Agatha for a divorce and she had rejected it. She didn’t believe in divorce but she was unable to find a way to break the impasse.

So everybody waited... and waited. It was nearly a week later before word came in that Christie might be in Harrogate in Yorkshire. Calder was able to learn that several staff and guests at the Hydropathic Hotel, one of the larger establishments in this old spa town, felt that one of their fellow guests, a Mrs. Teresa Neele of South Africa, bore a striking resemblance to the photos of the red haired Mrs. Christie published in the newspapers. Apparently this Teresa Neele herself agreed with other hotel guests that there was a resemblance to Mrs. Christie and they laughed it off, but all the same she took a keen interest in the latest newspaper reports on the search. Calder hurried up to Harrogate ahead of the police and confronted “Teresa Neele” in the Hydro Hotel before Christie’s husband got there to check for himself. The woman did not deny being Mrs. Christie, but claimed to be suffering from amnesia, a story Calder did not buy. As he later stated publicly, there was no “Teresa Neele” lurking in the self-possessed woman he met. This is supported by the fact that Mrs. Christie had apparently lost a diamond ring at Harrods in London the week before, and she wrote to them from Harrogate describing it and asking it to be forwarded to Mrs. Teresa Neele at her hotel, which Harrods duly did. She would have lost the ring as Agatha Christie, so why was it Teresa Neele who retrieved it from Harrods? Calder also discovered that she had a money belt on her, which not only explains her spending freely in Harrogate but also some premeditation. When Archie Christie arrived in Harrogate to identify his wife, courtesy of the Yorkshire police, she did not deny being Mrs. Christie, but she continued to claim she was suffering from amnesia and that she had no idea how she came to be in Harrogate.

Calder had no doubt that a gifted writer like Christie could pull off a stunt surrounding her disappearance. The press have always been a fairly cynical bunch, but that’s based on experiences close up with human nature, such as it is. Calder also knew that Christie had begun a relationship with Collins, a very savvy publishing firm, who knew the value of good publicity. Like most of the press, Calder assumed that the sharp intelligence displayed in The Murder of Roger Ackroyd must be at the root of her disappearance, and this was supported by a most unlikely source -- her husband -- in the week that followed. He declared to the Daily News: “My wife said to me, some time ago, that she could disappear at will and would defy anyone to find her. This shows that the possibility of engineering her disappearance was running through her mind.” The fact that he said this to the press upset a lot of people, but he had one advantage they didn’t: he knew he hadn’t murdered his wife. Archie Christie also told the press that suicide was not part of his wife’s moral philosophy of life and was therefore out of the question. Archie turned out to be right, though he was roundly criticized for his tactlessness, so the point is, she did know how to stage her disappearance.

Given the way things played out, is there any reason to doubt that the whole affair was a brilliant example of how to work the press, the police and the public? This “stunt” began gestation as Agatha’s coup de grâce to Archie, her way of saying “All right I will concede, but I will take you all with me.” The police behaved like her good Inspector Japp, dogged but lost up the garden path when faced with Machiavellian marital intrigue. But Calder thought that there was more to it and he began to wonder if he had been outfoxed and outclassed. As with other members of the press, he had focused floodlights on all the people who knew Christie, people she felt she could no longer bear – Archie, his family, their mutual friends. While he knew that Christie was deeply hurt by the breakup of her marriage and she desperately needed privacy, he could not help but notice that the effect was striking: it was all to her benefit. The public took Agatha’s side against her husband right from the start. How did she engineer that? Her husband certainly helped this along with his initial declaration to the press: “There is no question about the identity. It is my wife. She has suffered from the most complete loss of memory and I do not think she knows who she is. She does not know me and she does not know where she is. I am hoping that the rest and quiet will restore her. I am hoping to take her to London tomorrow to see a doctor and specialists.”

Why was the public so willing to give Christie the benefit of the doubt even when he described the cynical calculations of their creator in the newspaper – those strategically placed clues and the amnesia? Calder had to admire how it was done. While it succeeded in embarrassing her husband and it would engineer the eventual divorce on her terms, it was also a masterstroke of a publicity stunt that would enhance her career greatly.

After it was all over, Nancy Neele took herself off on a long cruise to duck reporters, and she married Archie once the Christie divorce went through in 1928. As for Mrs. Christie, she met and married her second husband, the archaeologist Max Mallowan in 1930 and she was much happier for it. Calder wondered whether they could all look forward to some of Christie’s forthcoming stories being about unfaithful husbands, their mistresses and wronged wives…

REVENGE

Mystery and crime writers took a different view from everybody else. Let us entertain the idea that Agatha Christie wanted to create more than a publicity stunt. Let us say, instead, that although she was emotionally distraught, she actually did stage the whole event primarily to embarrass her husband. That was the gist of Edgar Wallace’s piece for the Daily Mail during the 11 days she was missing.

Wallace wrote that this was “a typical case of ‘mental reprisal’ on somebody who has hurt her. To put it vulgarly her first intention seems to have been to ‘spite’ an unknown person who would be distressed by her disappearance. That she did not contemplate suicide seems evident from the fact that she deliberately created an atmosphere of suicide by abandonment of her car. Loss of memory, that is to say mental confusion, might easily have followed but a person so afflicted could not possibly escape notice... If Agatha Christie is not dead of shock and exposure within a limited radius of the place where her car was found, she must be alive and in full possession of her faculties, probably in London. It is impossible to lose your memory and find your way to a determined destination.”

At the moment Wallace wrote this, Christie may have been sitting in her hotel room with her feet up and a little champagne to celebrate how well things were turning out! She had planted her clues: several letters she had written before driving off into the night, one of them to her husband, and one of them to her secretary asking her to cancel her appointments for the following week. When she crashed the car she was fairly close to where her husband and Nancy Neele were staying. Was she driving there to spy on them, to satisfy in her own mind that her marriage was truly over? Did she crash the car deliberately within a reasonable proximity of their house to draw the media’s attention to it when she disappeared? And why choose the name Teresa Neele unless it was to ensure that her rival’s name became known all over the country? Hardly a coincidence. Archie Christie, who was known to hate “fuss,” now found his unfaithfulness slyly hinted at in every paper in the country.

Agatha Christie believed in Justice rather than the Law: in her heroes Poirot and Marple rather than policemen like Inspector Japp. Even murder was justified if it removed a more dangerous threat to society, and the idea is there in most of her novels, notably her final Poirot novel Curtain (1975), published the year before she died. She would have felt that Archie needed to suffer, not because he had personally betrayed her, which would have been purely selfish on her part, but because he had recklessly embarked on an affair and ended a marriage that, like it or not, was founded on the principles that held society together. She hated divorce and was especially concerned about the children affected by it. Does this make Christie a social conservative? Not necessarily, or perhaps only in the libertarian sense where individual actions may be morally justifiable if they right a wrong. The unfolding of events showed her to be an unselfish and ethical woman whose behavior was entirely praiseworthy. She just did it with greater style than most of us are capable of.

The mental breakdown story that followed was concocted for public consumption so as not to humiliate her husband and his family more than was necessary. It seems equally likely that the immediate family never knew her true motives, and she may never have confided in them, partly to avoid hurting them further and partly because she no longer felt she had to tell them anything at all. Let bygones be bygones. In this view, Agatha Christie’s disappearance was a defiant act of self-assertion directed at her husband and his mistress, of saying “HERE I AM. Do not think that I accept your desertion. I am a fighter and I resent being dumped for another woman.” This was a clear case of revenge but it was by no ordinary scorned woman.

AMNESIA

In any conflict of the human heart, there must be a place for psychological analysis that takes human frailty into consideration, in even the most intellectually determined individuals. When her husband asked her for a divorce, Agatha Christie felt a deep sense of humiliation at the impending destruction of her marriage and she felt a strong desire to withdraw from the scene of her pain. She wanted to get away from the place and the people who had hurt her the most. In a rather tragic way, this must also have meant her own daughter, Rosalind. She retreated to a place where no one would find her so she could rebuild herself emotionally, on the assumption that they would begin to look for her, and hopefully her husband would care enough to be in the lead. It was not to be.

One must remember that before all else, Agatha Christie disliked the press and she was painfully shy. In her autobiography, she refers to journalists as “faithful dogs” and “rats,” and she writes, “I had felt like a fox, hunted, my earths dug up and yelping hounds following me everywhere.” Throughout her life Christie was obsessively private. The very first sentence in Janet Morgan’s authorized biography is, appropriately, “Agatha Christie valued her privacy.” The publicity stunt and revenge explanations are just too super-rational to be taken at face value. One must remember that during the 1920s, the general public needed to lionize new heroes after the horrors of the Great War had eliminated soldiers as its heroes, and this helps explain why Lord Calder and Edgar Wallace were so keen to sensationalize their heroine and exaggerate her Machiavellian powers. Morgan points out that Calder’s claim to have “met” Christie ahead of the police is willfully misleading; indeed he may not have had an actual conversation with her at all.

One must look instead to the psychological explanations that emerged after Christie was found. Upon leaving Harrogate with her husband, she submitted to psychiatric examination, including hypnosis, and was able to fill in some of the gaps between wrecking her car and being found in Harrogate. The sequence of events was this: after the accident she walked into Guildford and caught an early morning train to London. She was dressed only in a skirt and cardigan, and she may have had some blood on her face. She had a cup of coffee at Waterloo Station and saw a poster advertising Harrogate spa, so she bought a ticket for there. Several doctors and a psychiatrist diagnosed this behavior as typical of a “hysterical fugue,” wherein an emotionally overwrought woman could experience a breakdown as a solution to her anguish. “For her future welfare she should be spared all anxiety and excitement,” they said. Psychiatrists examining the case in retrospect revised her condition to “concussion-fugue.” This condition can be epileptic, or traumatic (brought on by a blow), or hysterical (brought on by internal stress). Christie appears to have suffered from a combination of traumatic and hysterical fugues. If witnesses saw blood on her face when she arrived in Harrogate, this suggests that she was concussed by the accident in the car. It also explains why she left her warm clothes behind in the car. Combined with her already overwrought condition, concussion tipped her over the edge into acting out physically what her mind was unable to deal with. It is typical in such cases that the patient does not remember what she did, hence the amnesia. Morgan argues that people who have experienced hysterical fugues all have “a strong propensity to fantasize” and that Christie was “a prolific and ingenious fantasist... for whom the border between the real and the dreamt was thin.” “Imaginative, shy, intuitive, Agatha had all the characteristics of those who are capable of hypnotizing themselves at will. It was perfectly possible for her to have lost her identity and yet to have gone about the business of catching trains, shopping, and the like. Under unreasonable strain, deeply unhappy with herself, she might have induced a loss of memory.”

“In a first-rate work of fiction the real clash is not between the characters but between the author and the reader” - Ch14 of Speak, Memory (corrected)

The key to the enigma is Agatha Christie’s love of privacy. She refused formal interviews and public appearances throughout her life, and while this in itself is not so surprising, since so did other well-known women writers, it does suggest a deeper motivation. She wished to protect her private self, her writing self, the self that was traumatized by the death of her mother and the break-up of her marriage. This is all very English of course but it is also consistent with her emotional detachment from her characters. In a Christie novel, the puzzle remains central and you are unlikely to find Christie hiding in any of the characters. This almost deep-seated love of privacy kept her from fully engaging with the world around her and it helped produce the shattering events of 1926.

WHAT WOULD HARLEY QUIN HAVE SAID?

The truth of what happened in December 1926 is actually less interesting than the squabble that has developed over it since then. The more that is written about Agatha Christie’s disappearance, the less we know for sure. There is no official view on what happened and the biographers are split across the three explanations: the publicity stunt, the desire to get revenge on her husband, and the psychological breakdown. They are all persuasive and all three were probably true to some degree.

The trouble with either the publicity stunt or revenge theory on its own is that it turns Christie into some kind of Superwoman who controls events the way the author controls her characters. This argument is only persuasive if you believe that events luckily worked out her way and she was able to capitalize on them. Does this ever happen in the real world? Perhaps Lord Calder and Mr. Wallace had this kind of order in their own lives, but the rest of us do not, especially when we are emotionally stressed. Still, it is a view that some Christie biographers find convincing, even while conceding that she may have had a mild breakdown.

The Christie family, Janet Morgan and the majority of biographers, on the other hand, subscribe to the psychological breakdown theory. Morgan argues that she was much tougher and seasoned after this experience, but at the time, she was totally distraught at losing her husband. This theory has the disadvantage of robbing Christie of her strength, and turns her into a more passive figure controlled by her family, her in-laws and her biographers. The self-hypnosis story they have come up with is unintentionally patronizing. The situation cannot be explained away by saying Christie had a propensity for “fantasizing.” True, Christie was more than a little intrigued by the fictional possibilities of amnesia and hypnosis. However, there is no special reason to trust the family. They seemed overly concerned to head off the idea that Christie manipulated the crisis to inflict pain on others, including them. Morgan despises this view but it suits her purposes that Christie can be fitted into the ordinary woman box. Biography, like history, is a form of rhetorical warfare. In our hearts we all want to believe that our own book is superior to other people’s, for envy is the root of all literary evils.

We can also reject the suicide theory proposed in the Kathleen Tynan novel and Michael Apted film, Agatha. Suicide is not psychologically convincing because anyone who has wrestled with Christie through one of her novels could not believe she would ever think of suicide. Read her Harley Quin short story, "The Man from the Sea," published in The Mysterious Mr. Quin (1930). I think of it as her finest short story, a masterpiece that confirms her husband was right. She believed that suicide was not morally acceptable in a civilized society, and one should face up to one’s responsibilities without trying to destroy others. Furthermore, the Dustin Hoffman character is incompatible with all the available evidence. Agatha went to Harrogate to drink the waters of life, the aqua vivae, which like nepenthe could make her forget the past, or at least allow her to reconstruct her memory and her future along more practical lines.

In the end, Christie’s true success is as the disappearing author. Her disappearance in 1926 was an attempt to make time stand still for 11 days -- time enough for her to recompose her future life in the same way she composed her novels. Time did not stand still for others, of course, but it did for Christie. Having come to terms with her destiny she would go on to write books in which she would disappear in a clever weave of masks and magic tricks. All the great genre writers of popular literature have done this through the centuries, from fairytales to the modern horror film, with just as many of them intent on leading the reader astray as on instructing them on the right path. Christie’s mysteries are not inferior novels of limited psychological complexity; they belong in an entirely different literary tradition that has existed all along, parallel to the psychological tradition, and it doesn’t make any sense to compare one through the lenses of the other. Think the Bible rather than the Odyssey, the Gothic novel rather than Jane Austen, Alfred Hitchcock rather than Orson Welles.

In keeping with this, Christie did not like the rich set or the academics and intellectuals; she was an upper middle class and unsentimental pragmatist and she had a more powerful imagination than her detractors. She relished skewering post-imperial Britain with its White, Protestant and class-conscious society into which she injected the effeminate foreigner Poirot and the sneaky provincial busybody Miss Marple. Her heroes – including Harley Quin – snared the guilty and subjected that society to a critique of its own hypocrisy and its deceit, while also simultaneously feeling a deep affection for it. Intellectually she would turn to the Mediterranean world and the Middle East to find relief from the narrow provincialism that had become Britain. In retrospect it took the disaster of divorce to open her up to life’s rich possibilities. But she did live happily ever after.

MURDER IN MESOPOTAMIA

Traumatic events may take years before they surface in an author’s writing. Christie’s disappearance certainly appears to have surfaced in the work of others, whether it was intentional or not. Hitchcock’s film The Lady Vanishes (1938) and Daphne Du Maurier’s novel Rebecca (also in 1938) and the subsequent Hitchcock film, all turn on the fate of a disappeared woman. Both artists had to be aware of their more famous competitor’s crisis of 1926 and they give an ironic twist to the concept of disappearance, explored in the context of the thriller and the melodrama.

This was a time when the really interesting novels and Hollywood films had an ensemble cast, where anyone and everyone could be implicated in crimes of passion until someone sorted it all out. This could be a Hercule Poirot or a Miss Marple or some young innocent who stumbled across the scene of the crime. It was a time when those ensemble casts as often as not were internationally diverse, strangers in a strange land, a style that has been lost from much contemporary fiction and filmmaking.

But the real fascination lies, of course, in what Christie’s own writings tell us about her disappearance and how she viewed the charged dynamic between men and women, particularly the notion of revenge. Christie critics and biographers have not got very far in analyzing her mystery novels, looking for clues to the enigma of 1926. Yet, is there any reason to believe that she would not have done so, cleverly obscuring things of course, as one would expect from the Queen of Mystery? Her biographers, indeed her own husband, thought that the Mary Westmacott novels were the most autobiographical, but this is simplistic. These novels only confirm the theory that Agatha was the victim in 1926. No one has looked hard enough at her mysteries and studied what she has to say about revenge. This is not to suggest that Christie was a vengeful person; rather that she used her gift to explore her own feelings of resentment, her sense of violation – the powerful emotions that drive her best mysteries.

Murder in Mesopotamia was published in 1936, a full 10 years after the disappearance. On its surface, it is a classic Christie murder mystery but it is also one of her finest novels, with layers of cultural and historical commentary that transcend the narrow focus of her English village mysteries. It is a delicately woven tale of the English upper middle class tourist abroad in the wonders of the Middle East and it has many shrewd things to say about imperialism and racism. Christie was a woman who understood both these evils. Her best writing reveals she rejected them in her heart, although by and large her irony is misunderstood and underestimated by her critics on this point.

In Murder in Mesopotamia, Christie has written something that crosses the great divide between the genre work and the psychological novel and it sits half way between. Like the archaeology project that is the excuse for arranging an ensemble of suspects together, the novel arranges to have a dead body before too long and then sets off into the past, into the archaeology of a life, a personality. The character at the center, the murder victim, is Louise Leidner, a woman with a mysterious identity that becomes the center of the enigma. The other characters revolve around her, like extras in her play, even after she’s dead. She is a character in flux, continuously reinventing herself. This drives the others to distraction, since their own identities are destabilized by hers and they become like stage actors in her play, like Christie was at the center of her own mysterious disappearance. Louise is “a kind of female Iago,” says one character, for her puppetry behind the scenes. “She was a clever woman and she was bored and she experimented – with people – like other people experiment with chemicals.” “My God, though, that woman was an artist! There was nothing crude about her methods.” But was she so clever if she called death down upon herself at the hands of a vengeful ex-husband? In many ways, Louise is the very antithesis of Christie. Louise is a beautiful woman whom men find sexually magnetic, a woman compared with Keats’ La Belle Dame Sans Merci, endowed by Nature with a “calamitous magic,” says Poirot. Louise Leidner is a tragic figure. She could also be Nancy Neele. Christie herself had other charms.

Here then is Christie exploring feminine psychology with an autobiographical edge on it. She is Louise Leidner and she is also the figures of Amy Leatheran and S. Reilly and H. Poirot and the others who are the satellites around her. If all the world’s a stage, then this writer plays them all by turns, but they are only important for how they reveal Louise and who killed her. Poirot, like Christie, understands that the key to understanding the enigma is that feminine emotional problems of this sort are sometimes just a blind for the twisted male psyche that is manipulating her, just as Christie felt manipulated by her husband’s infidelities and the public embarrassment that she knew inevitably would follow her disappearance. That twisted male psyche turns out to be Dr. Leidner, who is not only her current husband but her ex-husband as well! Agatha tests the reader’s credulity a bit here: Leidner is the same man Louise had been married to for a few months back in 1918 when she was 20. She had betrayed that man to the authorities on the grounds that he was a German spy who had betrayed Britain. The story was that he had been executed but this was never corroborated. Shades of Mata Hari’s demise perhaps? Many years later, like Odysseus in front of Penelope, Leidner returns in a new guise as an American archaeologist, and with a partial disfigurement. Once satisfied that she does not recognize him, he awaits his moment to murder her. He still loves her though; this is a crime of passion. Leidner himself is like an empty space in the novel, in no way a target, just as Archie Christie avoided the limelight till it was focused on him. Behind the mask, Leidner, like Archie, wants to be rid of his wife and he turns out to be the real killer.

Isn’t that the real twist on the Christie divorce? This man wants revenge on the woman he was once married to, who had betrayed him for no better reason than because she wanted him out of her life. Flip the male and female roles and you have the Christie divorce. With a twist of the knife, we could say that Christie herself was also playing the Dr. Leidner role, savoring the revenge, and sticking it to her ex-husband. The implication here is that a mystery writer indulges in revenge. Christie is clever to disguise the machinery: Leidner is caught by another Christie persona, Hercule Poirot, and he too could be said to be Christie’s intellect and conscience. All this is revealed by a clever commonsense English hospital nurse, Amy Leatheran, who describes in resolutely chronological order what she failed to grasp as it unfolded at the time. The fairy tales woven around the Leidners are faithfully voiced by Amy, in characteristic Christie misdirection.

The second novel to look at is The Moving Finger (1942), published during the war years. This mystery novel is inferior to Murder in Mesopotamia because its misdirection is easier to see through, its setting does not have that sweep that you find in her novels set abroad, and her storyteller is not especially appealing, but it develops more fully a key Christie motif: poison pen letters. They had put in their first appearance in Christie’s The ABC Murders (1935) and then again in Murder in Mesopotamia, where Leidner used them to threaten Louise to prevent her from remarrying until he can snare her for himself. But poison pen letters are at their most nasty in The Moving Finger, which is suffused with the fears and phobias of war-time Britain.

Is the mystery novel itself a poison pen letter to the reader? Like Citizen Kane, these novels are at their best when they are – like poison pen letters – motivated by and directed at a real target, whether personal (Randolph Hearst, Archie Christie and Nancy Neele) or generalized (paranoid patriots, selfish egoists, unfaithful spouses). The moving finger picks at scabs and exposes wounds. This is archaeology of a different sort.

POISON PEN LETTERS

Poison pen letters can go beyond revenge; they can kill. The power of romantic obsession easily slides into the stalker who writes threatening letters or fires off text messages or posts a mortal threat on social media. Such messages gain greater power when written anonymously. If taken to their logical outcomes, they can literally kill.

Beethoven’s secret stash of letters to an apparently real-life Immortal Beloved never killed anybody. The fascination there lies in to whom they were addressed, not in who the letter writer was and how obsessed he was. Love letters falling into the wrong hands can lead to nothing more embarrassing than public ridicule, just as George Sand worried about her letters to Chopin being published. There were others who chose to avoid scandal altogether by concealing their lover’s identity in fiction.

Stefan Zweig’s story Letter from an Unknown Woman (1922) is different. In this story there is a secret admirer and her letters kill their intended target. In Max Ophuls’ film version of 1948, Louis Jourdan stars as a dilettante pianist and Joan Fontaine plays the young woman who is in love with him. One rainy night in Vienna, Stefan is returning to his apartment, knowing that he has a duel at dawn. He plans to avoid it by escaping town, just as he has escaped from commitments all his life. But a letter from an unknown woman has arrived that will plunge him into flashbacks. This letter, though written with love, is a poison pen letter, for it will result in his death, even if that is really not her intention. As he picks up the letter, Lisa’s voiceover begins: “By the time you read this letter, I may be dead.” Two hours later, when the movie returns the man to present time, everything has changed and he is engulfed in grief. He has lost a son he never knew he had and now a lover as well – possibly a true lover – and he realizes he never knew or appreciated what he had. But he should have known, and now that he does know, it is too late to do anything about it. He has been selfish. He has failed a test of his humanity – the capacity to experience romantic love – and this failing apparently can be fatal. If there is a simple symbol in the movie of the woman and her own fatal love, it is the white rose, a sad yet beautiful evocative image that recurs in the movie.

In this cynical age, it might seem a little over the top. Does anyone die for love these days? Maybe not very often, or maybe not often enough. The romantic imagination is undervalued. It has great power if you are young or nimble enough to indulge in it or if you are older and able to experience the nostalgia associated with lost possibilities, of love squandered, of the healing power of memories, perfumes and favorite songs. But many older people die from it, when one partner goes first and the other quickly follows. In Zweig’s own writings, it turned out badly: they turned into poison pen letters that ultimately killed him too, when he and his wife committed suicide, while in exile in Brazil. Agatha Christie would not have approved.